Unraveling Connections: A Comparative Analysis of Pali and Punjabi Linguistic Heritage

The Panjabi language has ancient roots. Clues in Buddhist scripture suggest it is at least as old as the oldest Buddhist text, the Tripitaka (Tipitaka). Alphabet pronunciation of modern Gurmukhi script is crucial for reading Pali scriptures. Panjabi script is also known by other names such as Patti and Pantee (35). Gurmukhi has roots in much older scripts like Takri and Sharada that were popular in the Punjab region for 2,000 years. Pali readers, maybe unaware, actually learn the sounds of Gurmukhi letters when studying the Pali language.

This article will explore the clues in Pali that shed light on importance and antiquity of Punjabi language, the significance of Shahbazgarhi in Punjabi linguistics and script, the Punjabi perspective on the Dhamma script controversy, and a brief introduction to the use of Punjabi in the Pali Canon and examination of evidence that Pali has a direct connection to the Indus region, including greater Panjab, but less so with Magadh or other eastern areas.

Panjabi – Punjabi language

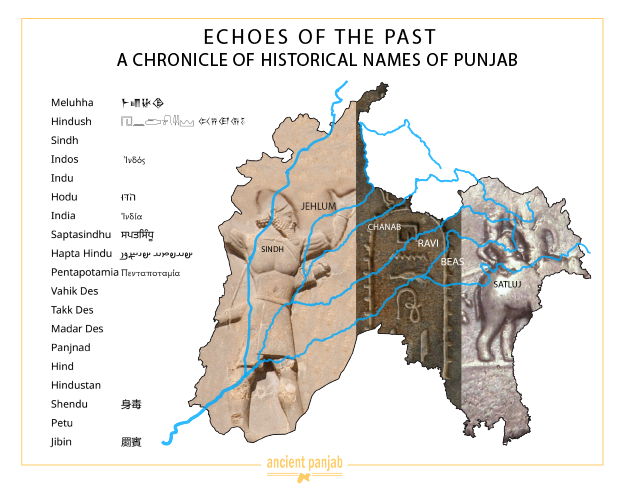

Panjabi is indigenous language of a vast region stretching between Afghanistan and Delhi. understandably, the language of Panjab is called Panjabi. This area, Panjab, is recognized as the cradle of one of the earliest civilizations in human history. It has been continuously populated for approximately 7,000 years. Harappa, the first urban settlement in the Indian subcontinent, is situated along the ancient banks of the Ravi River. The language of this region has undergone a continuous evolution over many millennia. While the contemporary term “Panjabi” is prevalent, numerous ancient and historical names for this area have been documented across various sources. See fig 1

The Panjabi language, when examined from a historical perspective, has undergone significant evolution and transformation, yet the modern iteration retains strong connections to its ancestral roots. Panjabi is classified within the Indo-European language family; however, the influence of this family constitutes only a minor segment of the Panjabi vocabulary. The predominant portion of the lexicon does not derive from Indo-European origins. Furthermore, Panjabi possesses unique grammatical structures and is characterized as a tonal language with a dual-gender system, distinguishing it from earlier Indo-European languages such as Vedic, Greek, and Persian, as well as from middle Indo-European languages like Pali and Sanskrit.

Pali

Pali serves as the linguistic foundation for the canonical texts of both Buddhism and Jainism. The Pali canon, associated with Theravada Buddhism (Way of the Elders), is acknowledged as the earliest comprehensive compilation of Pali literature. Similar to Sanskrit, there is a lack of surviving evidence for Pali scriptures. The similarities between Pali and classical Sanskrit are striking, as both languages share a comparable lexicon, grammatical structure, and historical context, rendering them mutually intelligible.

The chronicles of the Sarvāstivāda (“All Is Real”) school of Buddhism, indicate that the third Buddhist council, Mahasangha, convened in Jālandhara during the reign of Kaniṣka. During this council, various texts were recited to address and resolve the schisms among different sects, and commentaries (ਟੀਕਾ) on the scriptures were developed under the leadership of Vasumitra, who served as the council’s president. This was a very significant event, as it was during this assembly that the decision was made to compose scriptures and commentaries for the purpose of disseminating copies to stupas (reliquaries). This event took place in Punjab, and the linguistic characteristics of the region at that time must have impacted on the formation of the canon.

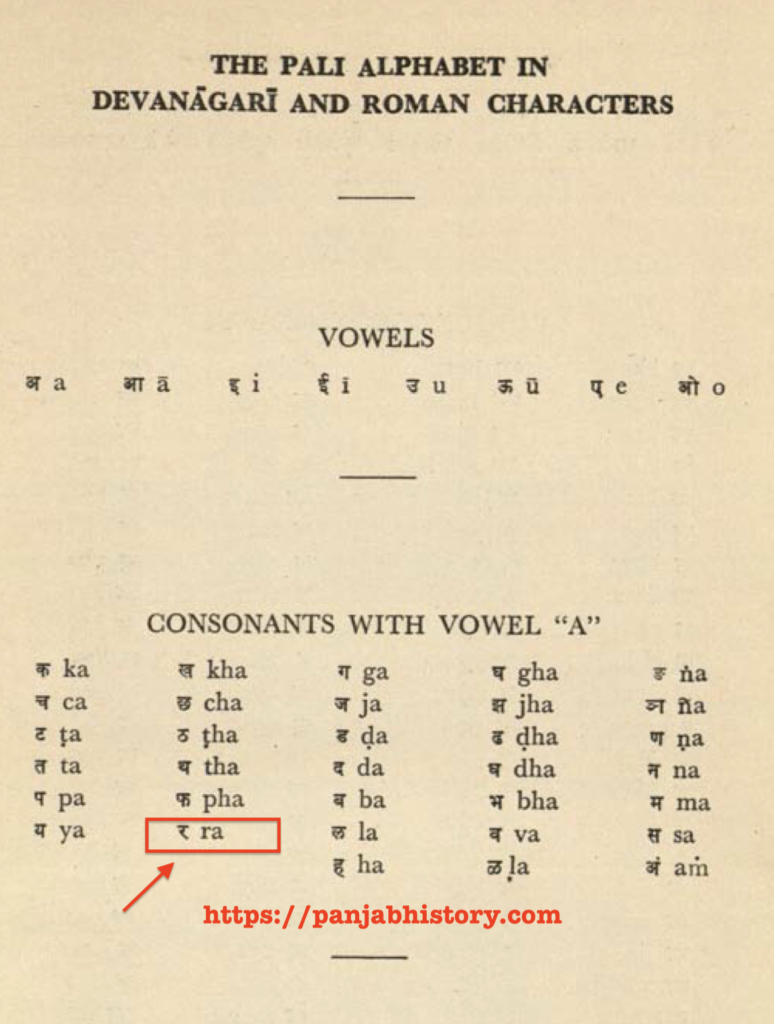

Importance of Gurmukhi Akhar (letter) pronunciation in Pali learning

To read Pali effectively, one must learn to roll the tongue as required for Gurmukhi letters. Kaa Khaa Gaa type pronunciation isn’t enough, one needs to learn Kakka, Khakha, Gaga. Pali scholar Bodhi Bhikkhu Jagdish Kashyap’s Tripitaka was published by the Bihar Government in 1959. It has a list of conjunct consonants for readers to understand Tipitaka. Please read here at the page before the contents. Mr. Kashyap has cataloged 30 sounds of modern Pantee as well as the consonant ਲ਼ (ळ) from the updated Gurmukhi script. See fig 2 These are undisputedly Gurmukhi pronunciations, distinct from Devnagri (Hindi or Sanskrit). Mastering the Roman alphabet is essential for English students, as it is the best suited script for the English language. Similarly, the Perso-Arabic script is essential for Farsi, Devanagari for Hindi, and Arabic Abbad for Arabic. Mature languages develop a script uniquely tailored to its needs. Pantee or Gurmukhi is the script for Panjabi. The ability to learn Pali by mastering the pronunciation of Patti ਪੱਟੀ, Pantee ਪੈਂਤੀ, or Gurmukhi letters also serves as direct evidence of the linguistic antiquity of Punjabi.

Micheal Witzel coined the term “Greater Panjab” to describe the ancient history of the Indus region. Prior to the large-scale migration of Turanic peoples, the cultural influence of the Indus basin plains extended as far as Balochistan, Kandahar, and Bamiyan in the North. Herodotus (484- 430 BCE) literally calls Kandahar region (Greek Arachosia, Persian Harahavati Vedic Saraswati) white Indians, Panjabis with whiter skin tone. India in those days was the name of modern Panjab. Which was situated between Gandhara and Thatagu (modern Sindh). There were 3 provinces situated on (and east of) Indus river, not all were called Hindu or Hind/India).

Importance of Shahbazgarhi inscription, R ਰ and SH ਛ tones

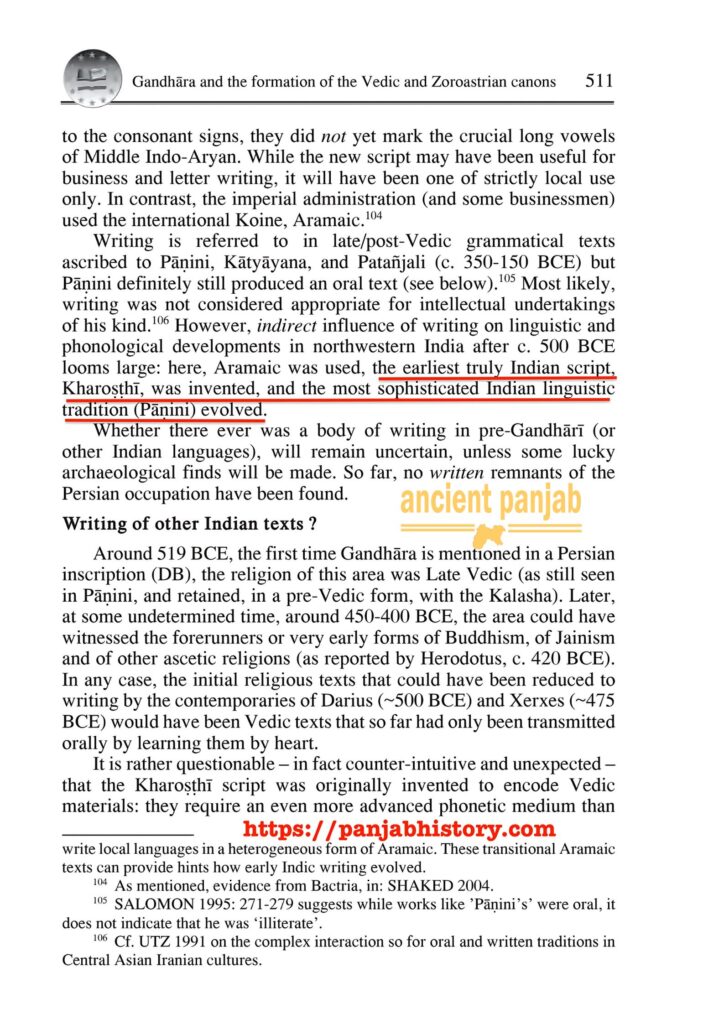

The Gurmukhi script of the Panjabi language is more than just another writing system, its letter pronunciations are part of a larger linguistic puzzle. The Kharosthi inscriptions of Devanampriya (Ashoka) found at Shahbazgarhi reveal the remarkable linguistic heritage of the ancient Panjab region. Harvard scholar Michael Witzel writes “the earliest truly Indian script, Kharoṣṭhī, was invented, (in Northern Indus region, Gandhara). {See figure 3} Kharoṣṭhī was first script to record local language. It’s important to mention before getting further into investigation.

Study of Asokan Edicts points out that the eastern inscriptions of Khalsi (UP), Dhauli and Jaugada (Orissa) are missing ‘R’, ‘ ਰ’ sound. ‘R’, ‘ ਰ’ is replaced with L (ਲ). Ranyo (Raja) is inscribed as Lajo & Lajina. The script used in regions East of Panjab did not contain the ‘R’ (ਰ) sound during the reign of King Devanampriyasa (Asoka). However, this sound is present in the Shahbazgarhi inscription from the upper Indus region and the Girnar (Gujarat) inscription. Further analysis of major rock edicts comes up with another fact that only Shahbazgari inscription has Sh (ਛ) tone. Sh (ਛ) is missing from Girinar, Khalsi, Dhauli and Jaugada major rock edicts.

The presence of the sounds Sh (ਛ) and R (ਰ) in the upper Panjab (Northern Indus) region, but their absence in the home territory of the greatest king, raised serious questions about how the Tripitaka could have been canonized in Magadh based on the local script, given that these two sounds were still missing 250 years after the writing of the Tripitaka. See fig 4 Scholars have unanimously abandoned the notion that the text was composed following Gautama’s parinirvana (death). While numerous new discoveries and hypotheses have since emerged, the canonization of Pali in the Magadh region (present-day Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) has now faded into obscurity.

The Pali literary tradition contains an abundance of words derived from modern Punjabi. These Pali words exist in their exact form only in the Punjabi language, and not in other Eastern languages. In fact, many of these words are exclusive to the Punjabi lexicon. This prevalence of Punjabi-origin terms is what makes the study of Punjabi particularly valuable for scholars of the Pali language.

| Pali | Panjabi | Meaning | Pali | Panjabi | Meaning |

| Accha ਅੱਛਾ | Accha ਅੱਛਾ | Fine | Jetha ਜੇਠਾ | Jetha ਜੇਠਾ | Oldest |

| Agg ਅੱਗ | Agg ਅੱਗ | Fire | Pakka ਪੱਕਾ | Pakka ਪੱਕਾ | Ripe |

| Amnb ਅੰਬ | Amnb ਅੰਬ | Mango | Raati ਰਾਤੀ | Raati ਰਾਤੀਂ | Night |

| Budda ਬੁੱਢਾ | Budda ਬੁੱਢਾ | Old man | Sikh ਸਿੱਖ | Sikh ਸਿੱਖ | Disciple |

Was Dhamm lipi original name of Brahmi script?

This is not a debate of Panjabi language enthusiasts. Brahmi and Dhamm are both scripts of East, and it is Purbias disagreement among themselves. The Panjabi perspective on this issue differs. The root of the controversy is that Brahmi’s true name is actually Dhamma lipi, as King Devanampriya (also known as Asoka or Ashoka) referred to the script as Dhamma lipi in his inscriptions east of Panjab. Shahbazgarhi inscription of Devanampriya is written in the Kharosthi script, not Brahmi or Dhamma. Heading east from Sindh river Topra, Haryana was the first inscription found in Brahmi or Dhamma script. West of Topra all Asokan and Kushan inscriptions were written in the Kharosthi script. Kharosthi was used exclusively in the Indus region (Greater Punjab) of the Indian subcontinent and as far as present-day Kazakhstan. The modern region of Panjab used its own unique scripts Kharosthi, Sharada and Takri, rather than the eastern forms of Brahmi script. The Shahbazgarhi inscription contains an important detail – it includes an exact line written in the Brahmi or Dhamma script of East. Applying the same criteria used in the Brahmi and Dhamma scripts debate suggests that the Kharosthi script should also be named Dhamma script. The debate between Brahmi and Dhamm is irrelevant to the Panjabi people.

Inscription line states the following verbatim.

Shahbazgarhi Kharosthi inscription

[aya] dharma-lipi Devanapriasa raño likhapitu

Girinar (Guajat) inscription

iy[am] dhamma-lipi Devanampriyena Priyadasina raña Lekhaalpita

Jaugada (Orissa) inscription

Iyam dhamma-lipi Devanampiyena Piyadasina Lajina likhapita

The Shahbazgarhi’s Kharosthi inscription uses the letter ‘R’ (ਰ) and the word ‘Dharma’ is used in place of ‘Dhamma’. This provides us with the first archaeological evidence of the word ‘Dharam.’ This inscription not only debunks the modern claim that Brahmi script should be called the ‘Dhamm script,’ as well as the notion that the word ‘Dharam’ originated from the Pali word ‘Dhamm.’ In fact, ‘Dharam’ was in use in the Greater Punjab region, while other areas outside the greater Punjab were still using the more primitive ‘Dhamm’ without the ‘R’ (ਰ) letter.

Analysis of Tripitka bring forth a struggle to accommodate R ਰ. Khudaknikaye starts with following famous Buddhist slogan

Buddham Sharanam Gachchami

बुद्धम् शरणम् गच्छामि

(I go to the Buddha for refuge)

Dharmam Sharanam Gachchami

धम्म शरणम् गच्छामि

(I go to the Dhamma for refuge)

Sangham Sharanam Gachchami

संघम् शरणम् गच्छामि

(I go to the Sangha for refuge)

The compilers of the Buddhist text Khuddaka Nikaya omitted the Kharosthi letter “ਰ” (R) when writing the word “Dhamma”, but included it in the word “shaRa.nam”. Similarly, the text uses the Kharosthi letter “ਛ” (Sh) for words like “GaShami”, even though this was not the standard spelling outside the Indus region during Ashoka’s time. It’s important to note that the Buddhist canon known as the Tripitaka (or Tipitaka) refers to the three “baskets” or collections of teachings, with “ti” meaning “three” and “pitaka” meaning “basket” ਪੇਟੀ in Pali. The Tripitaka was a written tradition, not solely an oral one. It is puzzling that the renowned ruler Asoka of ancient Magadha lacked access to the most sophisticated script to communicate his message in his home territory, when this advanced writing system was being in use in Panjab and already employed by Tipitaka authors 2 centuries before Asoka’s time. This discrepancy should raise intriguing questions for scholars of Punjabi linguistics. It also casts doubt on if language of Pali canon actually existed in Magadha. Especially the role of Panjab is grossly under researched when there is reference available that a major Buddist congregation on canonizing issue was held in Jalandhar, Punjab.

Ancient writing systems, now referred to as Brahmi and Kharosthi, were deciphered by James Prinsep in 1837. Until the 1880s, these scripts were commonly referred to as pin-man or stick-figure script, lacking a specific designation. The French scholar Albert Etienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie recognized these as Brahmi and Kharosthi lipi in a compilation of scripts cited in the Chinese Buddhist text, Lalitavistara. Prior to this, there was no recollection of any script existing in India. The names identified by Lacouperie continue to be utilized today.

Did Punjabi influence Pali ?

The notion that Punjabi originated from Pali is commonly proposed. Contrary evidence to this can also be found in the Shahbazgarhi’s Kharosthi inscriptions, which list traditional Punjabi words such as “dhee” ਧੀ (daughter), “doodda” ਡੂਢਾ (one and a half), “atdh” ਅੱਠ (eight), and “push” ਪੁੱਛ (to ask). These words are exclusive to the Panjab region and do not appear in any other languages. Similarly Kanishka’s Mankiala inscription in Kharosthi also employs Panjabi words. On other hand the earliest known evidence of Pali is a 9th century manuscript discovered in Nepal. Inscriptions from 6th-7th century Siam ( Burma and Thailand) contain some Pali terms, but there is a complete absence of such evidence from the Ganges valley, India.

The ancient Indian subcontinent utilized Prakrit languages in its numismatic and epigraphic records. However, the term “Prakrit” is a broad and imprecise label applied to the diverse indigenous languages of the region. Renowned scholars, such as Professor Charles Wileman, researchers from the Silk Road Project at UCLA Davis, the Dunhuang Project China and Hong Kong university are working to reverse-translate ancient Chinese Buddhist texts back into their original languages. The findings of these groundbreaking studies have been truly astonishing. Scholars have determined that both Sanskrit and Pali did not exist in Buddhist texts until the 4th century.

Buddhist monk Kumārajīva stands out in research. Kumārajīva’s father hailed from the Indus region, Kashmir or northern Punjab, while his mother was from Kucha, the modern-day city of Kuqa in China. Raised bilingual, Kumārajīva leveraged his linguistic expertise to translate a vast number of Buddhist texts from their original language into Chinese. Charles Wileman has reached at conclusion Pali and classical Sanskrit languages were just beginning to be incorporated into Buddhist literature during Kumārajīva’s era. His translations from older texts were from Gandhari Prakrit, the language of the Greater Panjab or Indus region. Gandhari Prakrit was an evolutionary precursor to the Punjabi language. However, if all texts prior to the 4th century were in Gandhari Prakrit, then it seems unlikely that Punjabi could have developed from Pali. In fact, the ancient form of Punjabi may be the root of Pali, rather than the other way around as suggested by some.

The 8th-century Prakrit poem “Gaudavaho,” authored by Vakpati, contains significant references. In stanza 93, he asserts that Sanskrit, Apabhramsha, Pisachi, and other languages derive from Prakrit. 11 centuries ago Kannauj’s Royal poet Vakpati had a deeper comprehension of regional languages than contemporary theorists. It is crucial for Panjabis to exercise caution regarding selectively chosen references. We should prioritize the original texts and refrain from depending on translations or subsequent interpretations. Please refer to stanza 93 on page 313 of Gaudavaho here.

Punjabi vernacular in Pali

Contemporary research and archaeological studies indicate that Pali must have originated from the indigenous languages of Panjab and the broader Panjabi cultural sphere. Pali like Sanskrit was literary language of Śramaṇa, Buddhist and Jain. Pali exhibits a somewhat less formal and more colloquial character. This can be inferred from the essence of the Sramana, who advocated for a lifestyle in proximity to the common populace, in contrast to the Brahmans. The native language of Greater Punjab significantly influenced the development of classical Sanskrit and Pali. Furthermore, reverse translations of Buddhist texts are likely to reveal additional intriguing findings for both inquisitive Panjabis and scholars engaged in this area of study.

Example:

The letter ळ is categorized as a consonant in Mr. Kashyap’s publication. The tone associated with ळ appears in Sanskrit, indicating very specific. Correct pronunciation of this tone is being debated, primarily centered on the tonal variations present in southern and non-Punjabi languages. In Gurmukhi, it corresponds to the tone of ਲ਼ (ਲੱਲੇ ਪੈਰ ਬਿੰਦੀ). In colloquial usage, it is articulated as a sound that lies between or combination of ਲ and ੜ or ਲ and ਡ. For instance, the word for hair in Malwai, Doabi, and Poadhi is pronounced as ਬਾਲ਼ rather than ਬਾਲ (bal), while cold is articulated as ਪਾਲ਼ਾ instead of ਪਾਲਾ, and the term for more or excess is pronounced as ਬਾਲ਼ਾ (ਬਾਅਲ਼ਾ) rather than ਬਾਲਾ (bala). This particular sound is also linked to the tonal characteristics of the Panjabi language. Among Panjabi speakers, its pronunciation is not contentious; however, it poses challenges for non-Panjabi speakers who may not be accustomed to tonal languages. The presence of ळ or ਲ਼ in Sanskrit and Pali, along with its contemporary usage in Panjabi, serves as direct evidence of the influence of Panjabi on these two languages, rather than the reverse. ळ or ਲ਼ (ਲਾਅੜਾ) is not an Indo European tone. It is not present in any ancient Indo-European samples. It can have only entered IE languages Sanskrit and Pali from the ancient form of Panjabi language at the initial stage of intermixing.

Indus region’s Kharosthi is the first script to appear in the Indian subcontinent. Michael Witzel notes no script existed in India prior to Kharosthi. (see page 511). It disappeared around the 4th century and was replaced with Sharda and then Takri became popular also. These both continued to evolve until the 20th century. Sadly now both have been wiped out by Devnagri onslaught. Multiple Lande and Gurmukhi also evolved out of these indigenous scripts. ( 1916 Grierson, Royal Asiatic society journal XVII) Gurmukhi has preserved authentic phonetics of letters the way they were intended to be used in Pali 2 millennia ago. New interest in Pali has also connected Gurmukhi or Patti-Pantee users to their ancestors when sages like Nāgasena and Vasumitra were born in this great region.

Conclusion

Bhikkhu Jagdish Kashyap has published a list of conjunct consonants aimed at assisting readers of the Pali Tipitaka (Tripitaka) in mastering the correct pronunciation of words. This list is fundamentally based on Gurmukhi or Patti/Pantee pronunciation. As previously mentioned, indigenous scripts have developed to optimally serve the languages for which they were created. In this way, Bhikkhu is subtly imparting Gurmukhi pronunciation techniques to those studying Pali. It raises an interesting question as to why other languages pronounce the letter K ਕ as “kaa” rather than “kakka,” as is the case in Gurmukhi.

Scripts are created primarily to accommodate their respective native languages, with vernacular taking precedence over script. The Devanagari alphabet has been developed to cater to the languages spoken in the Ganga Valley and regions of its influence. Punjabi, being a language of the Indus region, is most effectively represented by its own script. The application of this script in Pali, along with the historical significance of Punjab in antiquity, serves as indirect evidence of a closer relationship between Pali and Punjab. If Sakyamuni Gautama Buddha communicated in Pali, it can be inferred that he also spoke an ancient variant of Punjabi.

When individuals learn to pronounce K ਕ as “kaa,” the natural pronunciation of the word ਕੰਮ (Kamm) becomes “Kaam” (work). Gurmukhi has a direct connection to the ancient scripts of Sharda and Lande which were used to write Pali, and we continue to read and speak in the same manner, as exemplified by the teachings of Bhikkhu. Double consonant tones in the Panjabi language separates Panjabi from other languages. Gurmukhi script uses adhak ( ੱ) sign to incorporate double consonant ਦੂਹਰੀ ਧੁਨ. Pali has Akh ਅੱਖ, Sikh ਸਿੱਖ etc like Panjabi. These will become Aankh ਆਂਖ, Seekh ਸੀਖ in Eastern new Indo-European languages. Reason for this is in their script that evolved to accommodate their language. That why Devanagari letters are Kaa, Kha, Ga, when Gurmukhi letters’ pronunciation is full of double tones of Adhaks. Chacha, Shasha, Jajja and so forth. This is Panjabi’s critical connection with Pali, which no other language has.

Ramandeep Singh